Woodcuts and Sculpture

Sam Harrison brings a sensibility and a facility to making sculpture and woodcuts that is exceptionally rare. These capacities are significant alone but that they are combined with an acutely observational eye and a maturity suggest that Harrison is doubtless making some of the most engaging work by an artist in this culture.

Harrison's ability to convey the tension and resistance of movement, the grace and seductiveness of the body has developed beyond the drama hinted at in his 2010 exhibition. One thinks of the dynamism of Degas but more of the psychological drama associated with work by Spanish sculptor Juan Munoz and even the works of Portuguese painter and sculptor Juliao Sarmento.

The cynicism that pervades aspects of much contemporary practice, the glib approach to making, indeed to studio practice, has no part in Harrison's committed endeavours. It is his feeling and capacity to observe, his feeling for materials that sets his work aside. Between the polarities of Koons-like theatrics and preponderance of the lazy readymade that passes for conceptually based sculpture there is an important place for an artist like Harrison – an artist who deals in truth not riddle, material fact not recycling.

Despite losing access to his studio in the Christchurch earthquake, Harrison has pressed on making work in spaces made available to him; a barn in the country, a garage. Such is the uncommon mix of pragmatism and a relentless desire to continue making, that Harrison has produced one of the most compelling, potent and assured body of work in recent memory.

Harrison’s works are represented in numerous private collections around New Zealand as well as the public collections of the Wallace Arts Trust, Auckland and the Seuter Gallery in Nelson.

John Hurrell – 11 December, 2010

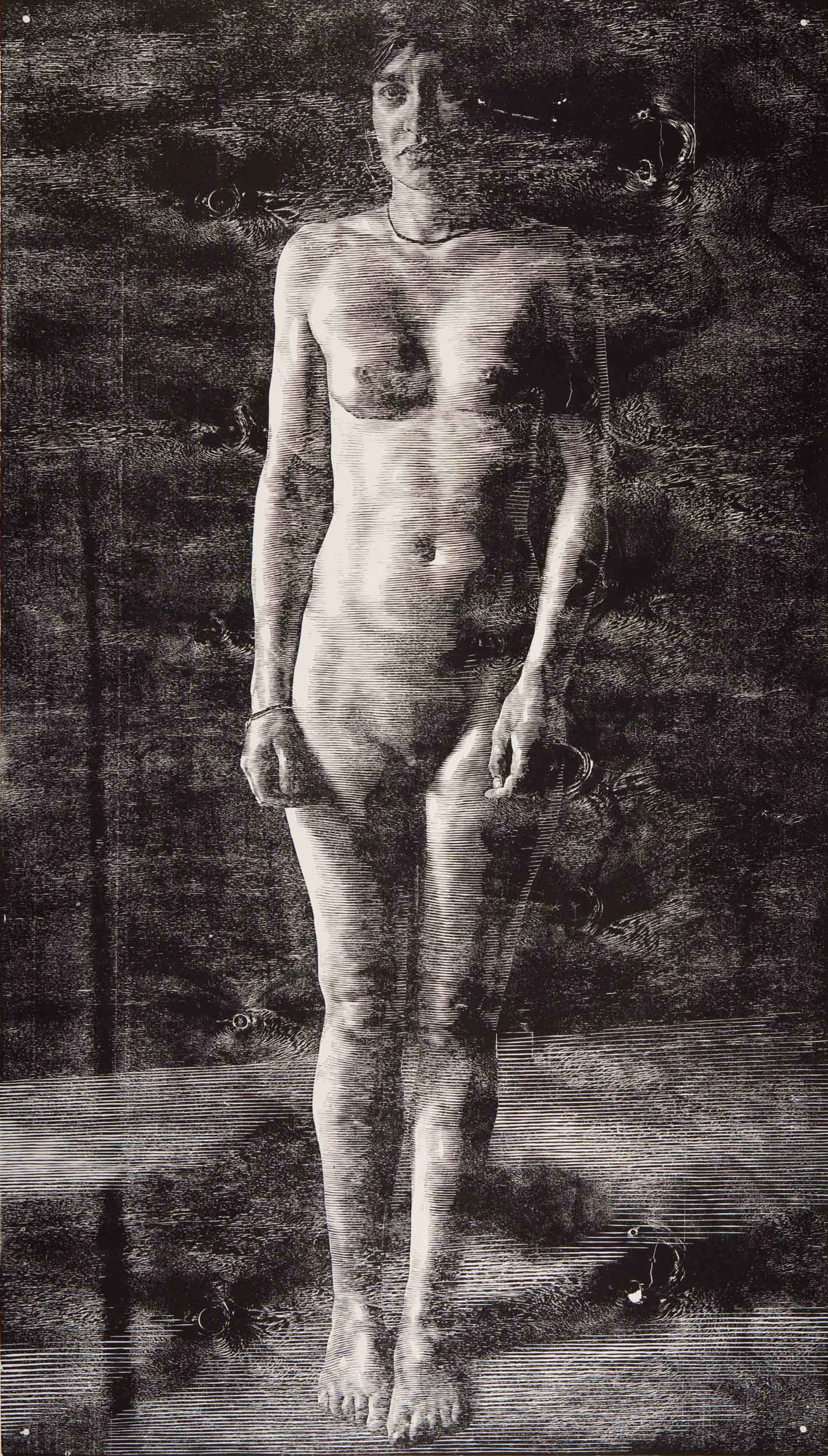

Harrison's horizontal hatching lines, drawn to articulate body shape and accentuate volume, disintegrate when mingled with the speckled properties of the grainy intaglio-applied ink. The lines of black Catherine Wheel-like flares, eclipsed knots-as-moons plummeting downwards in twos or threes, add real drama to these images.

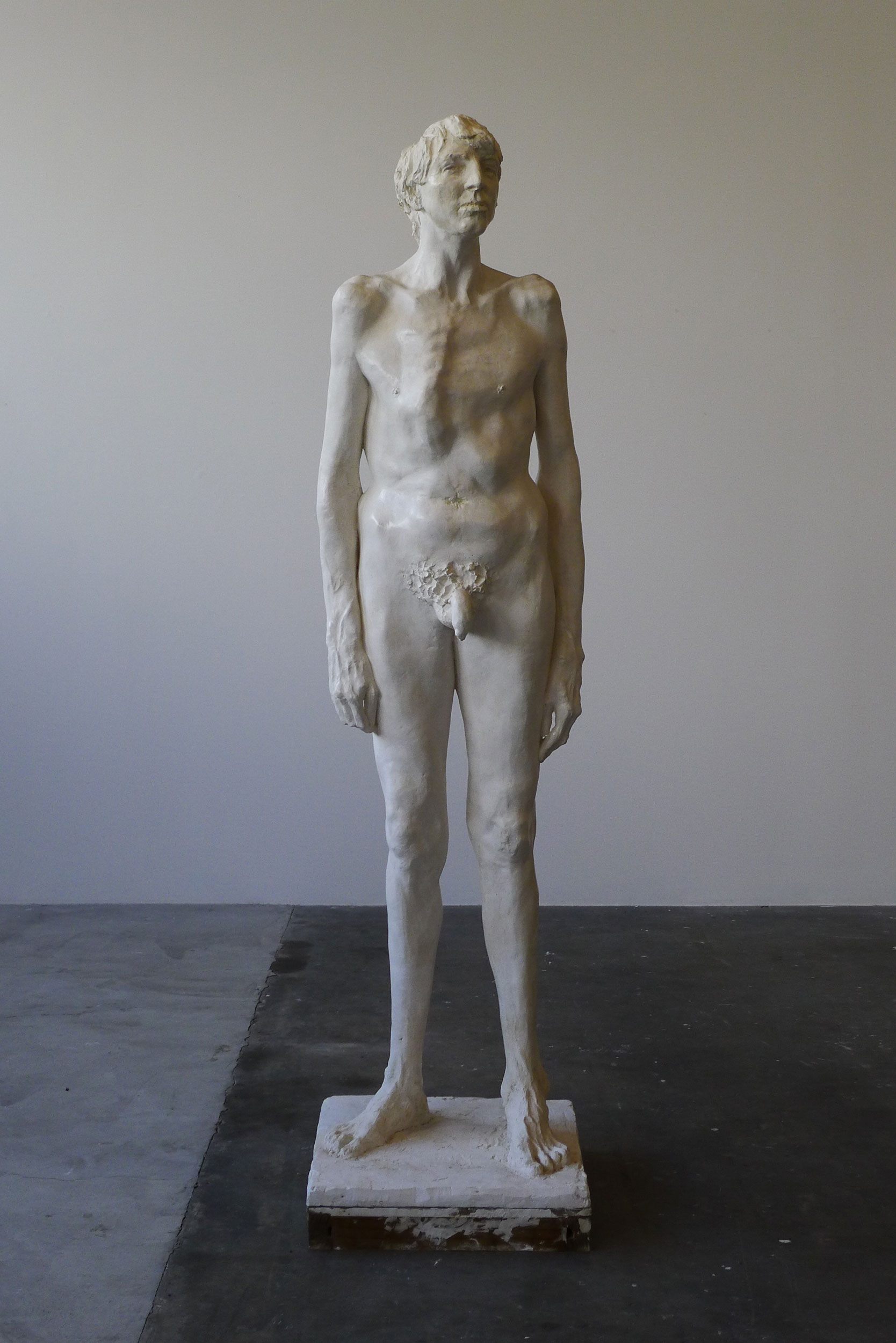

Sam Harrison - from Christchurch - has had his work presented before to Auckland audiences, particularly in Andrew Jensen’s Naked group exhibition, but this is his first solo show: three white plaster sculptures (not black as previously) and four woodcuts (three new). With the Ron Mueck show attracting big crowds in The Garden City, it is interesting to see some more nude sculpture up here from Harrison. These works, unlike Mueck, are not remotely attempts at realism (you’d never mistake them for the real thing, despite their accuracy in form), more a celebration of sculpture’s history and traditional subject matter. They reference a wide spectrum of art history from Rodin to Kiki Smith.

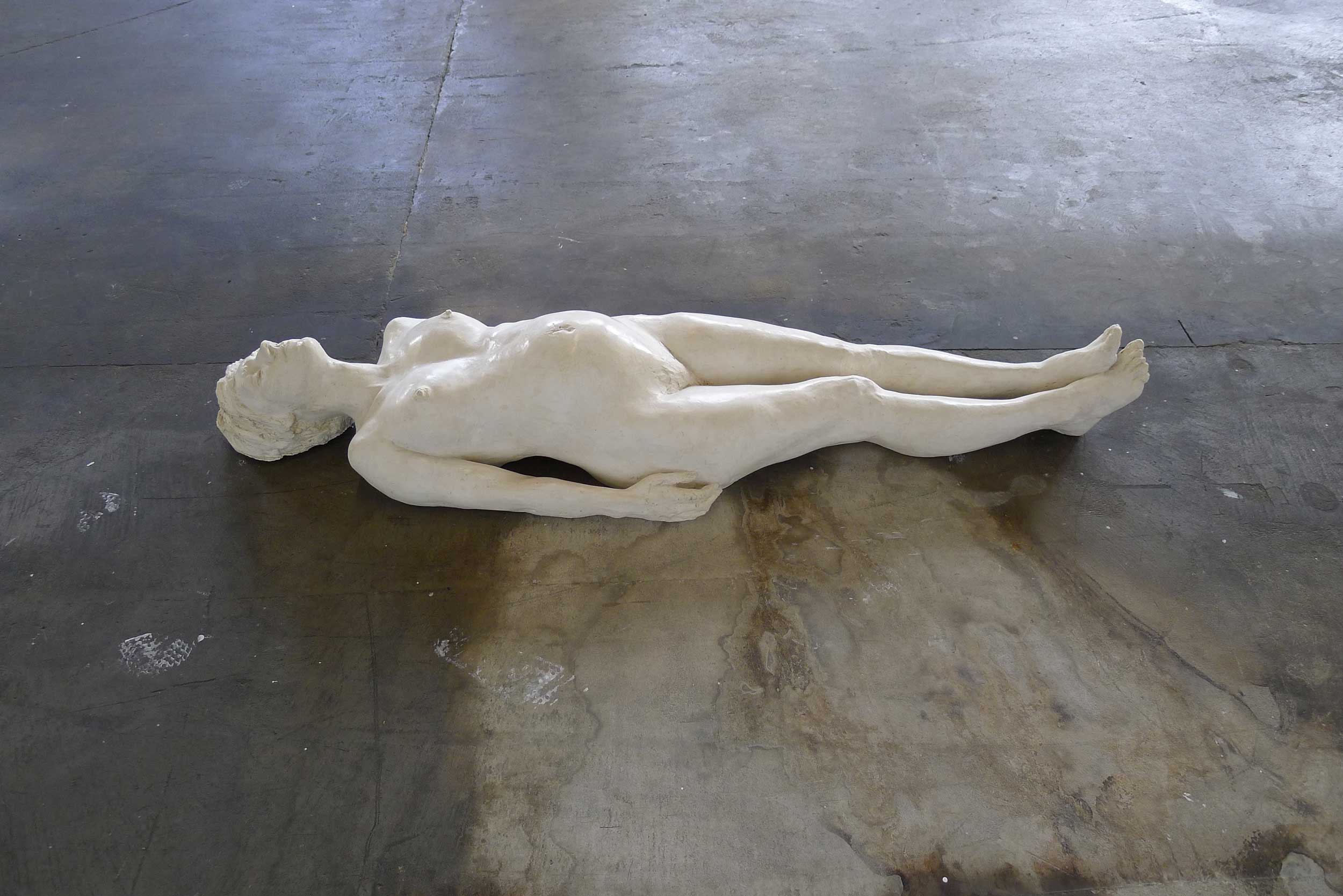

Harrison is interesting in that he plays off contrasting surface qualities - almost like a formal abstractionist. Some parts of the plaster bodies are shiny smooth and waxed so they look wet, other parts are dry, lumpy and raw. They have a gritty, crumbly coarseness in texture, especially around the extremities such as toes or ruffled hair.

A small, peacefully serene, pregnant woman, lying flat on the oil stained floor, is amazing with her small delicate feet and polished distended belly, while the bony fellow crawling on his knees, bum in the air, seems to be not so much grovelling as pounding the ground with his clenched fist.

The woodcuts are particularly successful because their images are more than just about chiaroscuro and (mostly) female figures interacting with shadow and light. The knotty splintery patterns of the gouged plywood have swirling vortices that cause ink densities to overlap and interfere with the clarity of the unclothed bodies - and partially obliterate faces gazing directly at the viewer.

Harrison’s horizontal hatching lines, drawn to articulate body shape and accentuate volume, disintegrate when mingled with the speckled properties of the grainy intaglio-applied ink. The lines of black Catherine Wheel-like flares, eclipsed knots-as-moons plummeting downwards in twos or threes, add real drama to these images.

The subjects of Two Women and Nellie, look confidently at the artist with a sense of gracious humour but in 19.26, the knicker- clad model is facing away towards a corner, her splayed knees push her ankles under her backside revealing the dirty soles of her feet. It’s a disturbing image, hinting at desperation, perhaps madness.

Vincent, one of the male models Harrison uses, is exceptionally tall, close to seven feet in height, and in the statue based on him his knobbly sinewy form has an oddly projecting right-hand rib cage that seems the result of some awful accident. The long horizontal woodcut of him lying in profile on his back - based on life drawing as with the other models - is a reference to Tony Fomison’s famous painting quoting Hans Holbein’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, a work that has also inspired a well known photograph by Paul Johns.

The white plaster sculptures from Harrison seem less compact than the earlier black ones, more linear without compression - the less nuggetty forms being easier to look at. However because of their haunting mystery, an enigmatic eroticism, the grainy woodcuts are the real stars of this show. They take your breath away through the relationship between coarse woody surface and contained inky image. They are amazing.

John Hurrell